Critical Thinking

Lesson 4: Reconsider

Objectives:

- Educators will be able to explain how logical reasoning strategies can be applied.

- Educators will be able to describe how costs and benefits can be considered to make decisions.

- Educators will be able to explain that decision-making is an abstract process with lots of potentially correct answers.

Objectives

- Educators will be able to explain how logical reasoning strategies can be applied.

- Educators will be able to describe how costs and benefits can be considered to make decisions.

- Educators will be able to explain that decision-making is an abstract process with lots of potentially correct answers.

We might not think of ourselves as detectives, but we solve mysteries every day. We all walk around with the awareness that there’s more going on than we can see. To make sense of our world, we take bits of information and piece them together logically to help create a complete picture. The more information we gather, the clearer the picture appears, allowing us to make the best decisions.

So far, in this class, we’ve focused on finding good sources of information. In this module, we’ll talk about how we can use all the information we find to draw conclusions and make informed choices through reasoning processes and decision-making strategies.

Logical Reasoning

We can use new information to help us make decisions by using logical reasoning strategies. While all the techniques you’ll learn about use information to help us support conclusions, the approach can lead to different outcomes.

In this section, we’ll look at two approaches. In the first method, we will start with a suspected answer and support it with known information. Then, we’ll look at two methods where we start with the facts, using them to draw likely conclusions.

Supporting a theory with known facts

Deductive Reasoning

In deductive reasoning, you start with facts that are presumed to be true and use them to draw a conclusion. Consider the example below.

Jan likes all types of cake.

Carrot cake is a type of cake.

Jan must like carrot cake.

In this problem, the conclusion checks out. Jan does like all types of cake, and carrot cake is a real type of cake.

But the problem with deductive reasoning is that when any part of the chain isn’t true, you can end up with a conclusion that follows the logical process but ends up being false. Consider this example.

Jan likes all types of cake.

Broccoli is a type of cake.

Jan must like broccoli.

While it’s unlikely that anyone would actually call broccoli a type of cake, you can see in this example how an untrue assumption can lead to a false conclusion. Deductive reasoning can be very helpful in applications like computer programming when a machine is being taught to follow clear rules, but when making tougher decisions, even what we would typically see as objective facts have a lot of gray area. Because of this, we should also consider an observations-first approach.

Using observations to form a theory

Inductive Reasoning

We can use observations to form a theory by using inductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning relies on patterns to help us infer what will happen in the future. Because the past is often indicative of the future, it can be a helpful strategy. Consider the example below.

You go to a restaurant and you like the dish you order.

When you return, you order the same thing again and you like it again.

If you return to the restaurant again and order the same thing, you will likely enjoy your food.

Inductive reasoning can be useful, as it leads to likely conclusions from observations, but it does have limitations. What if the restaurant gets a new chef who changes their recipe? Or what if they get a shipment of spoiled food and the meal is terrible? While we can’t use inductive reasoning to definitively predict the future, it is a great way to use new information to make educated choices. The best indicator of future behavior is past behavior; we just have to be open to new outcomes as well.

Abductive Reasoning

Another way you can use observations to draw conclusions is by using abductive reasoning. Like inductive reasoning, it relies on what we experience, but instead of relying on past patterns, it uses all available information to draw the best possible conclusion. The example below shows one application of abductive reasoning.

There is a long line at the movie theater ticket office.

There is only one movie showing today.

It is probably a good movie.

Abductive reasoning is common for professionals like doctors and detectives. It’s helpful for drawing conclusions with limited information. Abductive reasoning never leads to certainty, but as more information becomes available, specific conclusions become more likely.

Consider the example from before. You aren’t positive it’s a good movie, as there could be other explanations for the line at the box office, but it seems likely since there aren’t other movies playing. If you walk by and hear someone in line talking about how good they heard the movie was, that would make it seem more probable that it is a good movie. If you heard them mention how excited they were for a free popcorn promotion, that might make you question your original suspicions.

While inductive reasoning relies on the past and deductive reasoning relies on accepted facts, abductive reasoning is valuable as it allows new information to shape conclusions. By being open-minded to the effects of new information on our thinking, we won’t be as prone to bias towards our prior knowledge.

Analyzing the Costs and Benefits

While logical reasoning skills are great for evaluating information, we can organize additional relevant information about a situation through a cost benefit analysis. Watch the video below to hear about a Supreme Court case that came down to considering costs and benefits.

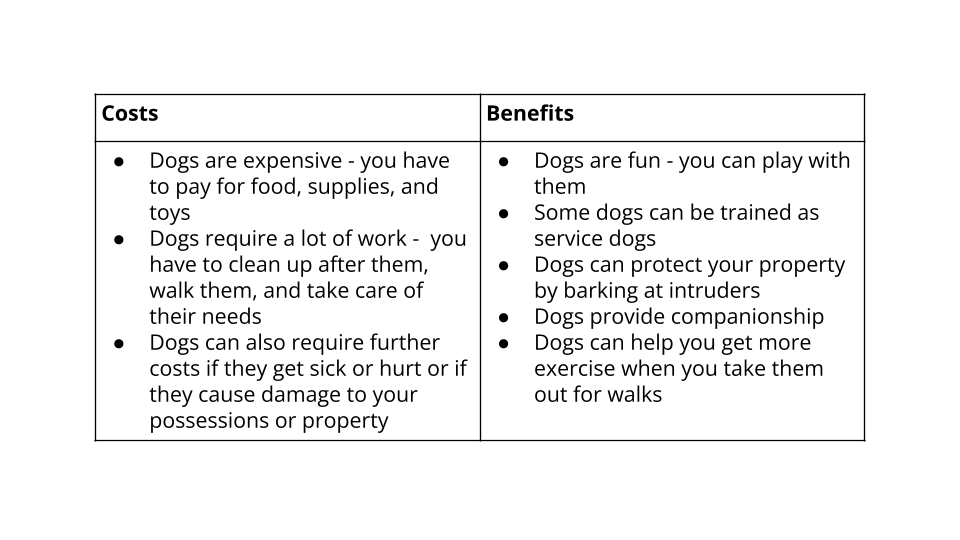

Cost-benefit analysis is a strategy for methodically listing the positive and negative outcomes of a choice. Costs and benefits may include things like money or non-monetary factors like time, quality of life, or the costs of associated risks. A t-chart, like the one below, can help us organize our thoughts about costs and benefits.

As you can see in the t-chart, cost-benefit analyses can help us think through both sides of an issue, but they are also abstract and can’t give us definite answers. In order to understand them as helpful tools, we must understand their weaknesses as well.

Comparing Apples and Oranges

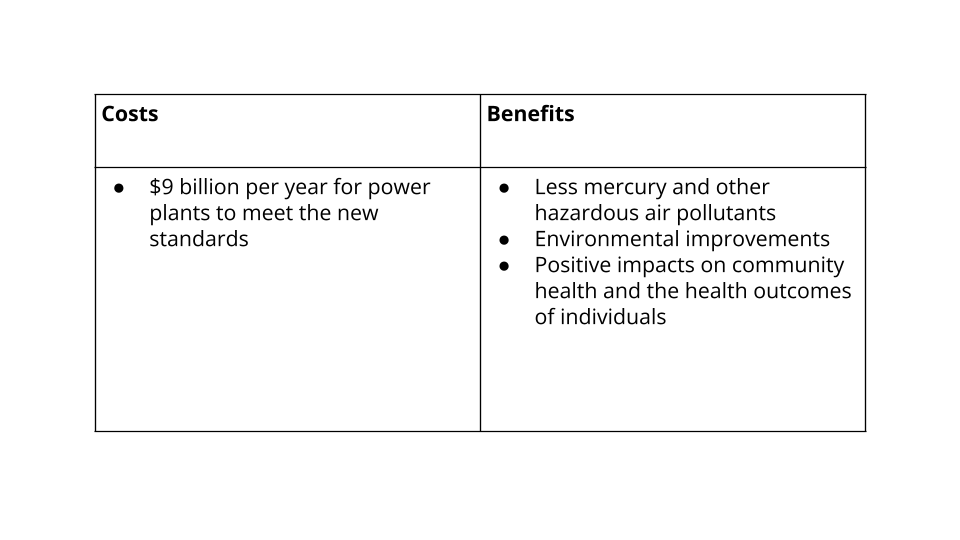

One major weakness of a cost-benefit analysis is that most things aren’t simple to compare. Consider the example from the video. Below is a chart of the costs and benefits of stricter regulations for coal and oil-fired power plants.

The left side of our chart has financial costs, but the right is made up of non-monetary benefits. The financial costs are heavy - they would put a significant strain on the coal and oil-fired power plants. But the EPA argued that the environmental and health impacts were far more important. While comparing money and lives seems cold, it highlights a key flaw in the strategy. When costs and benefits aren’t directly comparable, they start to be based more on opinion than fact. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t helpful. They still force us to look at the pros and cons of an issue. In the case from the video, the Supreme Court didn’t rule that the costs were more important than the benefits of stricter regulations; they only ruled that the costs must be considered when making major decisions. If you choose to use a cost-benefit analysis, think of it as a tool to help highlight both sides of an issue, not necessarily a definitive decision-maker.

Cognitive Biases Around Money

In addition to being hard to compare, cost-benefit analysis can become tricky because, as we learned in Module 3, we tend to experience cognitive biases. While costs and benefits aren’t limited solely to financial values, they often involve money. It’s important to be able to recognize biases that relate to money so we can be aware of them when making decisions. Explore the cognitive biases below to learn more.

Loss Aversion: A cognitive bias that causes us to see losses as more impactful than gains

- Example: Which do you think you would have a stronger reaction to: finding $100 on the street or realizing you lost $100? Most people would say the loss.

- Impact: The way our brains are wired, we are inclined to see losses as more important than gains, even when they are equal in value. Because we are loss averse, we tend to make decisions to avoid losses over making gains, which can lead to bias in a cost-benefit analysis.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy: A cognitive bias that causes us to include the costs of past losses in future decisions, even though they have no bearing on future costs

- Example: You buy a box of cereal at the grocery store, but when you have your first bowl, you realize it tastes terrible. Do you continue to eat the cereal, knowing that it’s gross, or do you throw it out? Lots of people would choose to eat the cereal, even though it would be unpleasant.

- Impact: In cases where costs have already been sunk, the only costs that should matter are future costs. When you compare costs and benefits, be sure to think about the future and not the past – we can’t change the past.

Do you think you’d fall for these biases? Try the activity below to find out.